Are You Carrying Someone Who Should Be Standing?—How Borrowed Functioning Keeps Relationships Stuck—And How to Change It

February 17, 2026

By Jennifer Finch, M.A., LPC, NCC, SEP

The term borrowed functioning comes out of family systems and relational psychology, most notably the work of Dr. Murray Bowen and later expanded by Dr. David Schnarch. Two of my psychology heroes since grad school.

I use this term with nearly all of my clients. And, it still holds up, despite its age, becoming widely circulated in clinical language in the 1970s. If anything, it may be even more relevant now as we witness our younger generations struggling more with leaving the nest on any sufficient timeline. Not only are they taking longer to leave home, but in learning to drive, launching careers, or really tackling any soft and hard skills that enable them to step fully into adult roles.

This article is not to diminish the pace of our youth of today, as borrowed functioning isn’t age-discriminating, but in a way, it can provide a bird’s-eye view into how the conditions around them have made independence more complicated. It certainly is not because they lack intelligence or potential. They are smarter, more driven, and more involved than anyone I knew when I was their age.

We can blame their apprehension and reluctance to go full force into their lives on many things, and I am certain it is even more complex than we can imagine. Economic pressures are real, and social expectations are constantly shifting beneath our algorithmic feet. Technology has changed and altered how we relate, work, and cope. All of that matters as we navigate the uncharted terrain, for ourselves and our children, and their children, too.

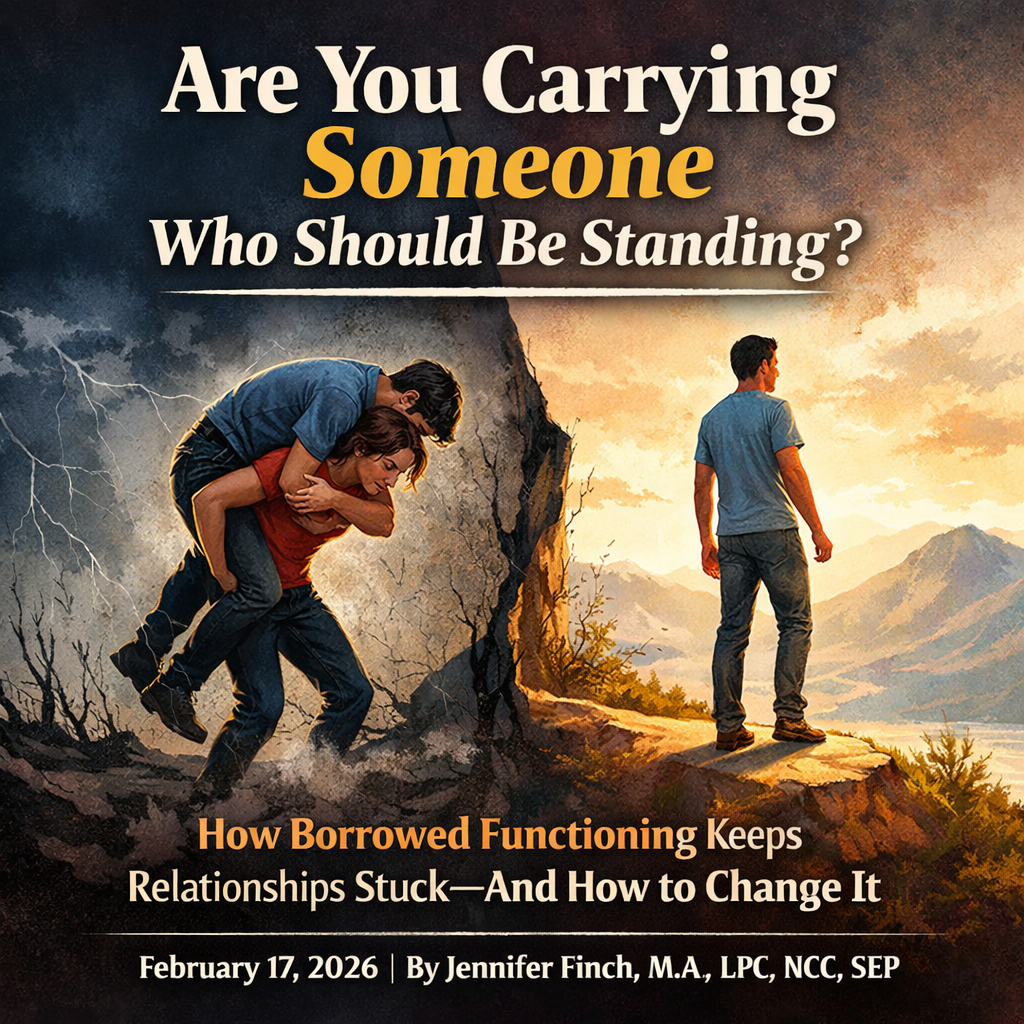

But alongside those realities, there’s another pattern worth naming, which is where I would like to direct your attention. It’s the pattern I’ve spent the better part of twenty-five years noticing and teaching about. It is the subtle transfer of responsibility and regulation that occurs when we begin to carry for one another what each of us, in time, must learn to carry for ourselves. This is called borrowed functioning.

Just like a sunflower instinctively grows towards the sun, the strongest source of light, a less-differentiated individual borrows functioning from others with a more defined sense of self. Just as the term suggests, they quite literally borrow functioning, like an externalized battery pack, and use it to charge up and regulate. The stronger, more cohesive individual is often, unbeknownst to them, helping the other consolidate their sense of self until that individual’s stability can take root. But often it doesn’t. It diminishes the moment you leave. Not unless they recognize they are the energy vampire in the room and running on borrowed power, without that awareness, they just keep looking for their next source, their next person to plug into. They will continue moving from source to source, looking for the next place to draw stability. Without a solid sense of self, it has become their survival pattern. This habitual pattern can hijack entire generations and carry forth for millennia until someone wakes up and realizes they don’t actually know who they are without needing to confirm it with someone else first.

Eventually, the process of maturation stalls. Development pauses, not in actual years, but in depth. To clarify what I mean by that, I am not speaking about chronological age here. I’ve met people well into their sixties and seventies who were never required to stand fully on their own ground. Someone has always stepped in to absorb the impact. Whether it be a parent, a partner, or, sadly, sometimes even their own parentified children—this type of role reversal is incredibly damaging and can take a long time to course correct.

Each rescue spares the borrower the immediate discomfort and anxiety to face on their own, but it also spares them the strengthening that comes from directly meeting the hard edges of life. Without those encounters at the razor’s edge of one’s capacity, the passage into fuller adulthood can remain indefinitely postponed.

Dr. Maria Montessori, founder of the Montessori method of education, captured this principle with remarkable clarity. One of her most cited lines is:

“Never help a child with a task at which he feels he can succeed.” Or how my kids rephrased this when they were young, “Help me to do it myself.”

She understood that unnecessary help, even when offered lovingly, can quietly interfere with the development of confidence and competence. The goal was never neglect, but right-sized support—assistance that respects a child’s capacity and strengthens it rather than replacing it.

Her insight translates well beyond childhood. When we step in too quickly, smooth every frustration, or carry what another person is capable of learning to carry, we may relieve discomfort in the moment, but we also interrupt the process by which people discover their own selfhood.

True support is not doing everything for someone. Nor is it shielding them from the wide and often intense emotional palette that is available within our human potential. It is creating the conditions in which they can do more, and feel more, for themselves, and trusting that the effort required to get there is part of what builds them.

Bless Our Hearts, This Isn’t Helping

Borrowed functioning often hides inside good intentions. It can be helpful…until it isn’t. Parents want to help, of course. Partners want to ease each other’s stress. Therapists want to be attuned and responsive. Teachers want to protect students from overwhelm. Yet when someone consistently steps in to manage what another person could learn to manage, especially emotionally, with effort, practice, and a tolerable amount of discomfort, the growth that would normally come from that effort gets postponed. The real tricky thing is that it can look generous, supportive, and it can even look loving. But over time, it becomes expensive for everyone involved.

The result isn’t laziness or lack of moral character. It’s a system that has redistributed responsibility. One person holds more functioning than they need to, and another holds less than they could. Over time, both become constrained and boxed in by the arrangement. One depleted, the other underdeveloped, neither especially free.

And this isn’t just a family or marital affair. You see this in any system. Corporate, academic, civic systems, schools, nonprofits, committees, spiritual communities, you name it, all have individuals borrowing functionality, and individuals overextending it. Any system under pressure will start redistributing functioning. A handful of people step up and keep everything moving; a larger group orients around them and never quite has to. Someone once told me that 100 percent of the work is done by 10 percent of the people. I don’t know if the math is exact, but the fatigue I’ve seen across nearly every setting suggests the pattern holds. There are far fewer internally anchored adults than there are people still leaning on someone else to keep the structure upright. And the few doing the carrying are tired. So this is the not-so-subtle invitation to put down what was never yours to haul in the first place and start moving differently. That doesn’t mean withdrawing care or refusing help when it’s genuinely needed. It simply means offering support without becoming the entire support system. You can be kind without becoming the infrastructure.

How It Works

In a borrowed-functioning system, one person becomes the external, surrogate nervous system for another. They think for them, soothe for them, decide for them, anticipate for them, and often absorb the discomfort that growth would otherwise require. The person receiving the support feels relief in the short term. The person providing it feels useful, needed, and in control. The system stabilizes. Temporarily.

When this reaches a critical threshold, every relationship begins to organize itself around avoiding activation rather than building capacity. What began as care has now turned into a form of incapacitating dependence.

This is why the concept still matters. It appears wherever anxiety is high and differentiation is low. And right now, we are living in a climate saturated with both. It shows up in therapy rooms and trainings, classrooms, organizations, and online culture.

It gives us language for a dynamic that we are already feeling within our families, relationships, workplaces, and even institutions. It helps us ask where support is building capacity and where it might be replacing it. And it reminds us that real confidence doesn’t come from being carried. It comes from discovering, often gradually and imperfectly, that we each individually can carry more than we thought. But we have to trust in the other’s capacity to do just that.

Many of our systems are quietly contracting under the weight of borrowed functioning, leaving people feeling less capable and more fragile than they truly are. I share a growing concern about strands of language within the trauma field that, while well-intentioned, can inadvertently reinforce a sense of fragility rather than the resilience that is also inherent in us. But I’ll save my fuller thoughts on that for a future article, preferably one written after a strong cup of coffee and with my sense of humor intact, because this is a conversation best had with both care and a little levity.

So, Who’s Fault Is It?

The problem is, and if you are reading this, you probably know already, that being someone’s source eventually burns you out. When you live in a state of overextension, carrying more than what is actually yours to carry will eventually extinguish your own light. And when I say carry, I am not talking laundry loads. Although doing a twenty-five-year-old's laundry would count. I am talking about the energy load of the anxiety and tension that lives underneath. When we try to hold the emotions steady within another individual to keep them functioning, it becomes a slippery slope for our ability to hold our own. A simple check is to ask: Am I trying to keep someone “fine,” and “happy,” because if they feel anything else, or hear any bad news, they will fall to pieces, and I will have to pick them up from the pile they are now in on the floor?

What started as care and a reasonable expectation of safety and stability within a relationship will turn into strain. And if we are not careful, it can lead to the river banks of resentment. And even worse, drowning in regrets. And resentment is much harder to recover from. It is where natural vitality dims and dies. And, well, we all know the tattooed saying about having, “NO REGRATS.”

But, before you say, “that’s why I feel so burned out,” or “that’s why I am no good at adulting,” the exhaustion doesn’t belong only to the one who overfunctions. Borrowing someone else’s stability is tiring in its own way. It requires constant orientation outward. Watching, waiting, gauging how others are doing in order to know how you are doing. It keeps your footing dependent on conditions you can’t control. Over time, that arrangement becomes just as draining, because it never allows the deeper confidence of self-trust to take root. The borrower has to learn how to venture out into the big, wild world and tolerate the discomfort of anxiety and tension that it most certainly will provoke. Facing fear and learning how to fail better will accompany that.

Ultimately, there is no fault line. Both sides are implicated in the pattern, and both have a role in changing it. This isn’t about blame. It is about responsibility. Of Self. And learning how to hold onto it without compromising your own energy.

The one who gives too much must learn to step back and tolerate the anxiety and tension of not fixing, not smoothing, not cajoling, not carrying. They must also learn to witness the borrower's anxiety and tension without intervening. So in a way, they have to let go of two loads—the others’ anxiety as well as their own.

How to know if you are in need of dropping two loads: If witnessing someone else in suffering makes you uncomfortable so much so that you now have their anxiety as well as yours coursing through your body, this is a clue you are a battery pack for others.

As for the one who leans too heavily, they must begin to take on more of their own weight, gradually building a solid-flexible sense of self and cultivating the strength that comes from doing so. This is Olympic training in distress tolerance in an anti-fragile way. My best advice here is: if you fall down seven times, get up eight.

At some point, the system has to shift. Even if only one person decides to change, it will force a two-choice dilemma into the system. The balance cannot stay the same. So, the relationship dynamic is forced into a choice. Either remain organized around limitation, or grow. And growing pains, are well…painful. So we must tolerate that as well.

The good news is that when someone becomes more differentiated, more able to stand on their own ground, they gain freedom. They stop organizing themselves around another’s instability, and the system must respond. If it doesn’t, both parties risk remaining small and contracted.

The ones who differentiate first often leave behind those unwilling to grow. Well-differentiated individuals will be the first to outgrow dysfunctional systems. Not to state that this is a competition. There is no finish line and certainly no trophy waiting for whoever reaches maturity first. Remaining compassionate and open-hearted to those who cannot tolerate growth or change is imperative. But you can accurately predict that once you can stand on your own two feet, it becomes harder to keep participating in arrangements that depend on imbalance. The reward isn’t applause. It’s freedom. That freedom comes with the ability to stay connected without being pulled back into the very patterns that keep everyone small.

When two people stand on their own and borrowed functioning ceases, the system can expand, mature, and make a genuine connection possible. But this real connection hinges on the work done individually. Telling the other individual to do their work defeats the purposeful instruction here and will likely end in tensions escalating. Well-differentiated people don’t need to be right or in control of what others do or don’t do. Their stability isn’t at stake. Because their solid-flexible sense of self is internally anchored, the behavior of others no longer defines them or determines their footing. They can stay present without needing to manage, correct, or secure agreement in order to feel intact. They are free of all that. They are mature adults.

When neither person is collapsing nor compensating, and each can remain steady and emotionally responsible for themselves through self-soothing and self-regulation, such stability increases resilience across the whole system and it can now balance in equanimity.

It is a hard thing to do. This is by all means, easier said than done. Remaining steady within yourself while staying connected to others requires insight, courage, real persistence, and tenacity. It is, in many ways, the name of the whole relational game.

Think of it as an ongoing practice in which you might always be in training. It is one you can return to again and again, as there will be ample times throughout every given day that provide opportunities for practice and growth. This is a practice that, by its own nature, can not be perfected, but we can get better. Practice makes better practice, I suppose. Each time you choose to hold onto who you are without overgiving or overtaking, you interrupt patterns that once felt inevitable. Slowly, over time, with patience, something steadier will bloom and begin to take shape. A way of relating in this maturity is both self-respecting and kind. If there is a part of you that longs to stand firmly in your own life while still loving well, let that be enough to begin. From there, a more sustainable and compassionate way of living together becomes possible.